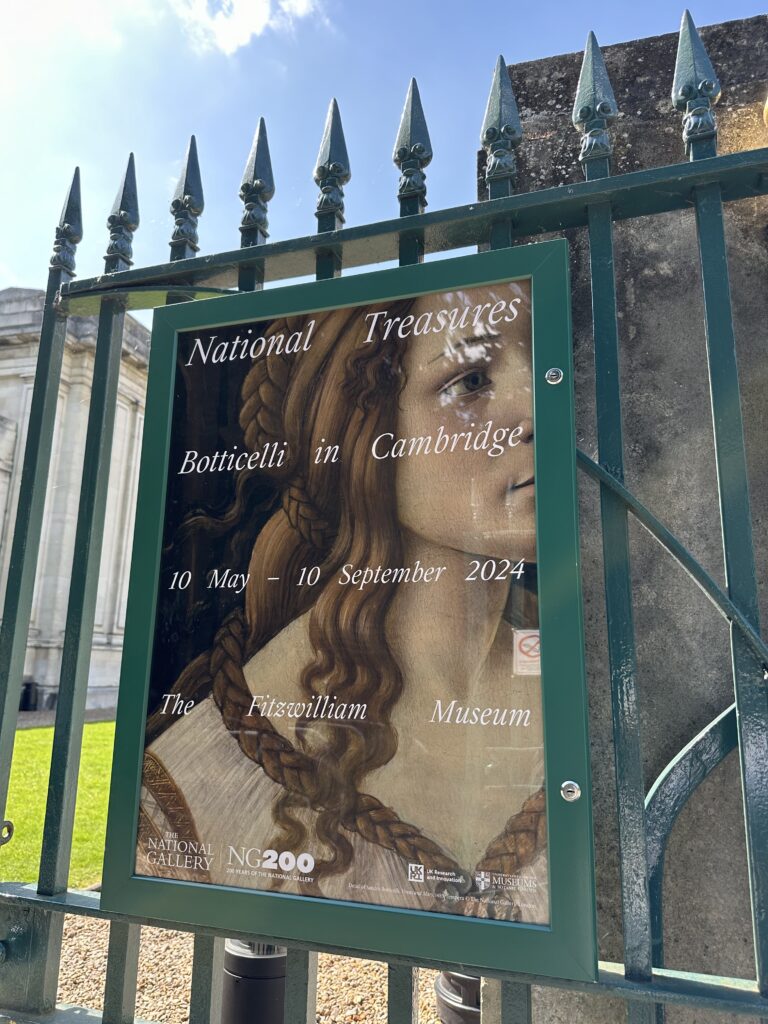

2 June 2024, The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

8 June 2024, The National Gallery, London

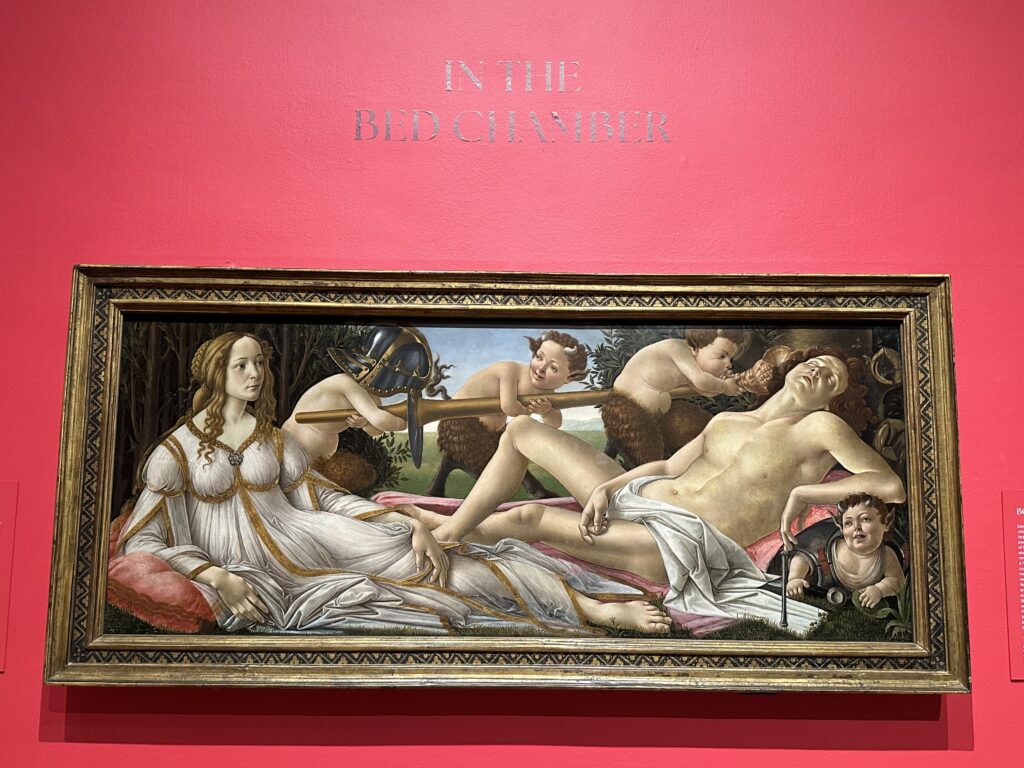

Sandro Botticelli’s celebrated painting, traditionally entitled Venus and Mars, is spending the summer at the Fitzwilliam Museum. It is lent for the first time ever by the National Gallery in London.

Sandro Botticelli Venus and Mars, 1485, tempera and oil on poplar wood, The National Gallery (photo private)

Sandro Botticelli’s success was due in large part of the backing of the rich and powerful Medici family. He fused inspiration from classical Roman art and mythology with the freshness of emerging Italian poetry.

This unique blend gave birth to his iconic depictions of women—ethereal figures embodying poise, virtue, and an alluring mystique that would come to define a new standard of feminine beauty in art.

Mars and Venus, one of Botticelli’s masterpieces, exemplifies his ability to weave complex narratives into visually stunning compositions. The work is layered with rich symbolism. Mischievous satyrs playfully interact with Mars’ discarded armor and weapons, a metaphor for love’s ability to disarm even the god of war. Venus, portrayed with serene composure, provides a striking contrast to the vulnerable, slumbering Mars.

This juxtaposition powerfully illustrates the central theme: love’s capacity to pacify and dominate war.

Charles Fairfax Murray The Flaming Heart, 1863, oil paint on panel, The Fitzwilliam Museum (photo private)

The Victorian era imposed rigorous standards of beauty and morality on women. They were expected to be the moral compass of their families, embodying virtue and purity.

Charles Fairfax Murray’s The Flaming Heart exemplifies these ideals while drawing on rich symbolic traditions. As a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Murray’s work is distinguished by its meticulous detail, vivid colors, and themes inspired by literature, mythology, and history.

This painting is a potent symbol with deep roots in religious art. Often associated with the Sacred Heart of Jesus, it symbolizes divine love and compassion. Murray’s use of this potent symbol in a secular context creates a fascinating interplay between religious iconography and Victorian ideals of feminine virtue.

The muse of this painting, Annie Miller, was a captivating figure who enthralled artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Before her discovery by the group, Miller lived in poverty, working as a barmaid.

Recognizing her potential, the Pre-Raphaelites took Miller under their wing. They sought to refine her, offering lessons in literacy and etiquette. However, their mentorship soon evolved into a complex dynamic. The artists became increasingly possessive, engaging in fierce rivalry for Miller’s affections.

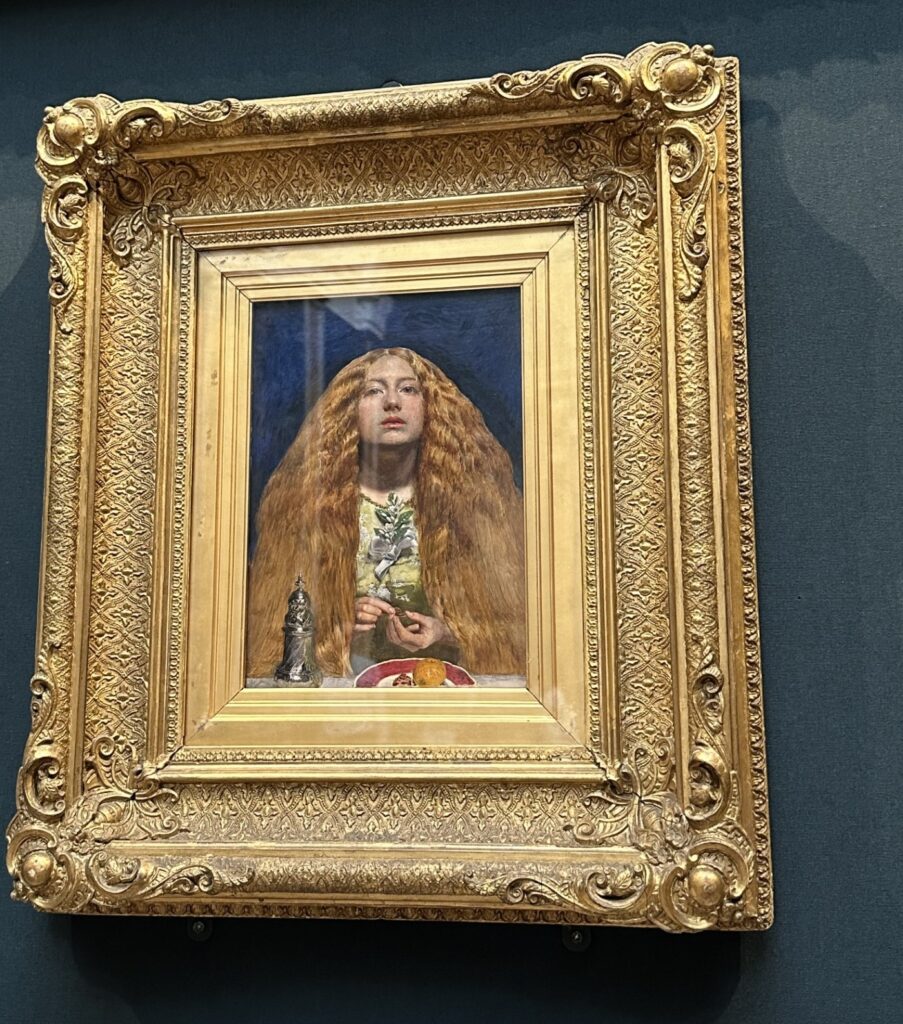

John Everett Millais The Bridesmaid , 1851, oil paint on panel, The Fitzwilliam Museum (photo private)

This painting presents another portrayal of the idealized Victorian woman.

The scene depicts a bridesmaid performing a popular superstition of the era: passing a piece of wedding cake through a ring nine times, believed to summon a vision of her future husband.

Symbolism abounds in the details. The orange blossom pinned to her chest is a traditional emblem of chastity, while her luxuriant hair signifies youthfulness and fertility—qualities highly prized in Victorian women.

The subject’s expression is particularly telling. Her look of blank self-absorption suggests a sense of surrender to her presumed destiny as a wife. This vacant gaze, coupled with the ritualistic action, underscores the societal expectations placed on young women of the time.

Quinten Massys, An Old Woman (The Ugly Duchess), about 1513, oil on oak, The National Gallery (photo private)

This painting markedly deviates from the idealized forms prevalent in the Italian Renaissance. An Old Woman exemplifies grotesque portraiture, serving as a stark counterpoint to the period’s idealized depictions of beauty and virtue. After seeing this painting, the unforgettable image lingers in my imagination.

The subject’s exaggerated features—her deeply wrinkled face, bulbous nose, and sagging breasts—stand in direct opposition to Renaissance ideals of youth, symmetry, and proportionality, as seen in works like Botticelli’s Venus and Mars.

Intriguingly, the woman appears to be presenting herself as an object of desire, holding a rosebud-a symbol of passionate love. Perhaps she is looking for a lover. This unexpected detail adds a layer of irony and complexity to the already provocative image.

The painting’s enduring appeal stems from its bold exploration of themes such as aging, vanity, and the nature of beauty. By portraying a figure who brazenly defies every canon of beauty and rule of propriety, Massys challenged artistic conventions of his time.

Through this unconventional subject, Massys invites viewers to question societal standards of beauty and the value placed on physical appearance, creating a work that remains thought-provoking centuries after its creation.

Photos by Marc Lauterfeld