16 June, 2024 Venice

The Venice Biennale 2024 was an unforgettable experience. Now, I’d like to share some of my reflections and key observations on the remarkable artworks I encountered.

This year’s Venice Biennale, titled Stranieri Ovunque- Foreigners Everywhere, runs from 20 April to 24 November, 2024, curated by Adriano Pedrosa and organised by La Biennale di Venezia. Adriano Pedrosa (Brazil) is the first Latin American to curate the International Art Exhibition.

The expression Stranieri Ovunque has several meanings. First of all, that wherever you go and wherever you are you will always encounter foreigners-they/we are everywhere. Secondly, that no matter where you find yourself, you are always truly, and deep down inside, a foreigner, explained Adriano Pedrosa.

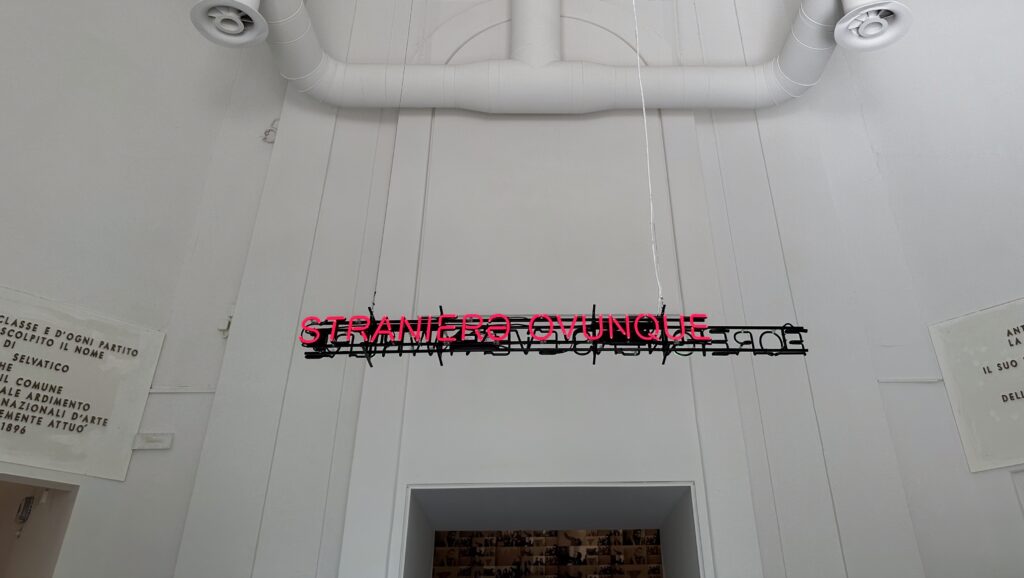

Installation view of Foreigners Everywhere (2004) by Claire Fontaine (photo private)

Stranieri Ovunque– Foreigners Everywhere, the title of the 60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, is drawn from a series of works by the French collective Claire Fontaine, a woman and a man, a couple now based in Palermo, but originally founded in Paris.

They have been making neon sculptures since 2005, which read, in different languages, the expression ‘foreigners everywhere’. They are written in over 50 languages-Western languages, non-Western languages, Indigenous languages; some, in fact, are extinct.

Claire Fontaine in turn appropriated the expression from the name of another political-activist collective from Turin in Italy that was fighting racism and xenophobia in Italy at the beginning of the 2000s.

The exhibition addresses deep themes like immigration and cultural diversity and exploring the complexities of living in a world scattered with wars and humanitarian crises.

Art and Espresso at In Paradiso Cafe

Located at the entrance to the Biennale Gardens. The In Paradiso Restaurant has always been a meeting point in the heart of Venice. A crossroads of intellectuals, artists, people from all corners of the world.

During the coffee break, the friendly owner showed me the collection of photos of prominent visitors including the legendary Peggy Guggenheim. To my delight, I spotted the photo of Okwui Enwezor, an art critic and curator I admire.

Spanish Pavilion

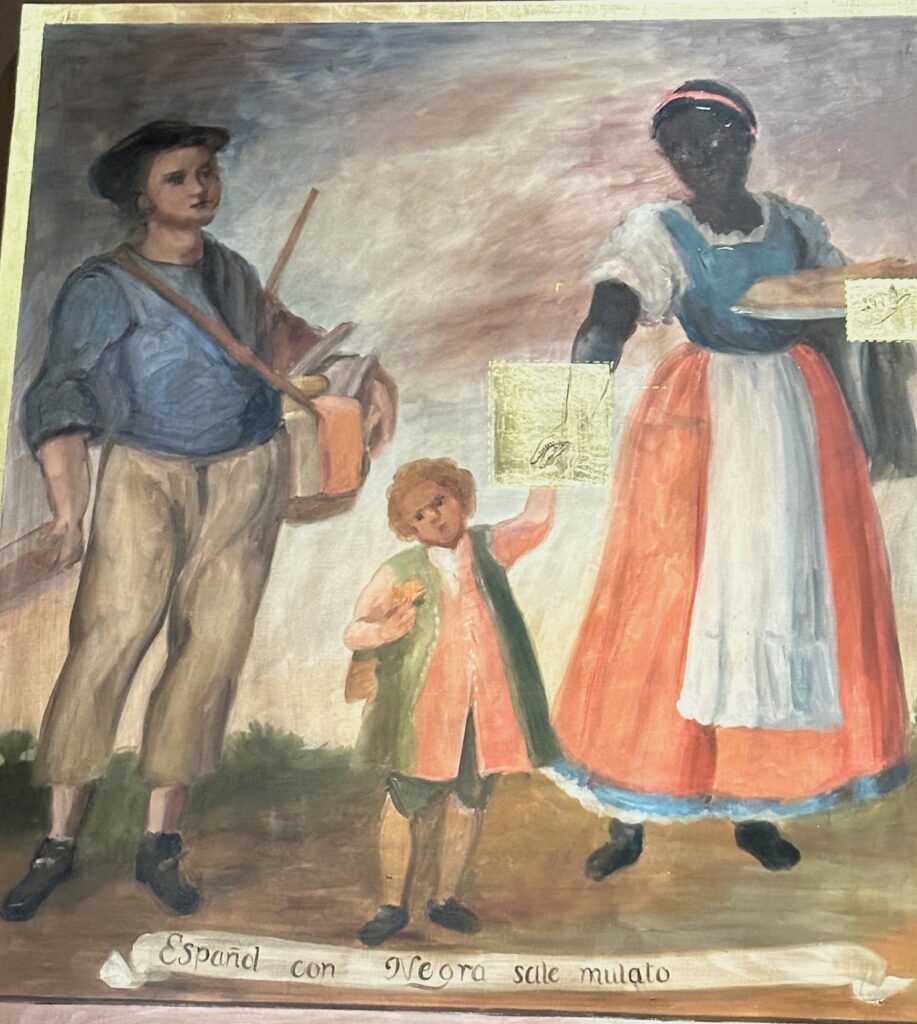

Pinacoteca Migrante, Migrant Art Gallery (When the Streets Speak), 2024 by Sandra Gamarra, red iron oxide, oil, gold leaf, imitation gold leaf, and press clippings on canvas

The Peruvian artist Sandra Gamarra Heshiki, represents Spain at the Venice Biennale. It is the first time in 60 editions that an artist not born in Spain has done so. Her project, Pinacoteca migrante, an imaginary museum with a range of paintings and a small critical number of sculptures, questions colonial narratives and historical modes of representation. She explored the classic genres of the arts: engraving, portrait, landscape… with interventions and reinterpretations that will analyze the biased representations between colonizers and colonized.

Migrant Garden

Sandra Gamarra Heshiki, Racism Ilustrado I (Pintura de pastas y trabajo reproductivo) Enlightened Racism I (Painting of Castes and Reproductive Work) 2024, oil and imitation gold leaf on canvas (photo private)

Casta paintings, a genre prevalent in colonial Latin America, reflect a concern with purity of blood. While ostensibly documenting the diverse racial mixing that occurred in colonial society, these paintings ultimately served to reinforce a rigid social hierarchy. The term “Casta” itself referred to the Sistema de Castas, an elaborate system of social stratification that granted significant privileges – economic, social, and political – to those of European descent.

A large terminology was devised to categorise those who were at the lower position of the hierarchy: not just mestizo, but also castizo (a light skinned mestizo), mulatto (a person of European and African descent), morisco (light-skinned mulatto).

It emerged from a desire to maintain European dominance and control. The origins of this hierarchical system can be traced back to the conquistadors themselves, figures like Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro, who fathered children with indigenous women, further complicating the social and racial landscape.

While seemingly driven by an Enlightenment-era spirit of categorization and classification, the Cabinet of Illustrated Racism illuminated a story about how anthropology and science were used as a tool of racial discrimination.

Korean Pavilion

Korean Pavilion, Giardini della Biennale (photo private)

Koo Jeong A’s artistic practice delves into the profound connection between scent and memory. This exploration has been a central theme throughout her career. The artist has often drawn inspiration from personal experiences, such as the aroma of mothballs, a scent inextricably linked to her grandmother’s cupboard. This distinctive odor transcends cultural boundaries, resonating across generations.

At this year’s Venice Biennale, Koo presented Odorama Cities within the Korean Pavilion, a project that introduced an immaterial dimension to the exhibition. This “scent landscape” aimed to create an invisible portrait of the Korean Peninsula, translating individual memories into olfactory sensations.

Through an open call inviting participants to share their “scent memories of Korea,” the artist gathered over 600 personal narratives. Collaborating with Seoul-based perfumer ‘nonfiction’, these memories were transformed into a diverse array of fragrances, immersing visitors within a unique olfactory experience within the Korean Pavilion.

Immaterialism, weightlessness, endless and levitation are the four keywords mirrored throughout the Korean Pavilion. They are embedded and engraved as infinity symbols directly into both the wooden floor and the outdoor installation, are manifested as two floating wooden möbius-shaped sculptures and a levitating, scent diffusing bronze figure KANGSE SpSt (2024).

Koo Jeong A, KANGSE SpSt, 2024, bronze (photo private)

In an interview, Koo expressed a desire to challenge the conventional notion of a nation. By employing scent to represent the Korean Peninsula, the artist sought to transcend the physical division of the country, fostering a sense of unity and togetherness through shared memories and sensory experiences.

Scent has no borders.

Benin Pavilion

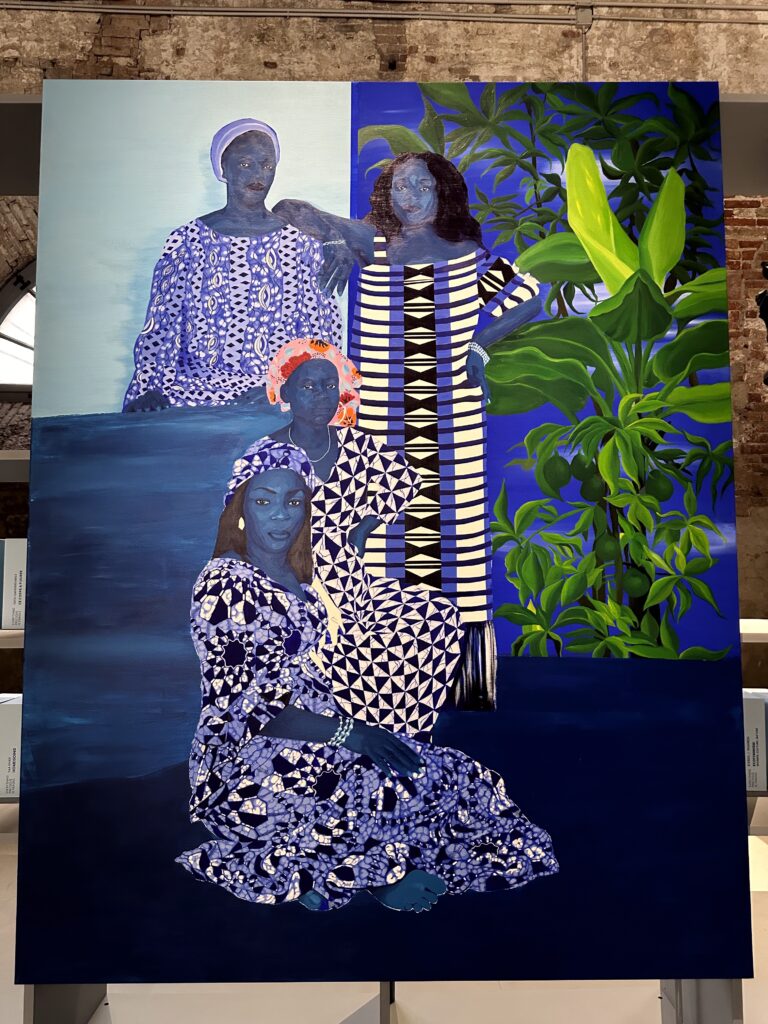

Moufouli Bello, Egbe Modjisola in Everything Precious Is Fragile, Pavilion of Republic of Benin (photo private)

This year, the Republic of Benin opened its first pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale, titled Everything Precious is Fragile. The pavilion features artists Chloé Quenum, Moufouli Bello, Ishola Akpo, and Romuald Hazoumè. As curator of the first-ever Benin Pavilion, Azu Nwagbogu explains the conceptual heart of the pavilion, which is fruit plucked from several trees; one of feminism, one of indigenous knowledge, one of ecology, one of Benin’s history, and one of Benin’s future.

During his research, the etymology of the word gèlèdè comes from ‘everything precious is fragile.’ Nwagbogu thought that was such a powerful line. And just like that, he had found a title for the exhibition.

Nwagbogu explains that gèlèdè is a Yoruba tradition surrounding the veneration of the mother: ‘The men would wear clothing and put on a mask and perform a dance to honour the mother, to honour women and the wisdom they hold.’ Therefore he wanted to use gèlèdè to deal with this issue of epistemic injustice and violence.

Moufouli Bello, Egbe Modjisola in Everything Precious Is Fragile, Pavilion of Republic of Benin (photo private)

Moufouli Bello uses traditional large-format indigo-tinted portraits, showcasing the iconic Yoruba patterns found on women’s clothing and designs of blue dyed fabric.

This lawyer-turned-visual artist delves into the complexities of womanhood in Beninese society, exploring both the desires and limitations faced by women while simultaneously highlighting inequality and injustice.

Bello’s portraits, where women gaze directly at the viewer with an arresting intensity, invite contemplation on identity. These captivating works, saturated in blues, are deeply influenced by the artist’s childhood experiences with gèlèdè, a revered Yoruba-Beninese ceremony honoring motherhood through traditional dance and spiritual practices.

Arsenale

Yinka Shonibare’s work frequently incorporates ‘African’ fabrics, a material with a complex and intriguing history. While often associated with Africa, these vibrant textiles actually have their origins in Indonesia. Initially produced by the Dutch for the Indonesian market, their popularity waned by the late 19th century. Seeking new markets, the Dutch shifted their focus to West Africa, where these fabrics were embraced and now represents the African identities.

Yinka Shonibare, Refugee Astronaut VIII, 2024, fabreglass mannequin, Dutch wax printed cotton textile, net, possessions, astronaut helmet, moon boots and steel baseplate (photo private)

In 2010, Shonibare’s Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle, was installed upon the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square. By using African-inspired patterned cotton textile for the sails, he is making an allusion to the transatlantic slave trade. His work is clearly intended to problematise imperial history.

Born in Britain to Nigerian parents, Shonibare’s upbringing was privileged. His great-great grandfather was a Nigerian chief, and his father a lawyer. As he has mentioned in interviews, he didn’t grow up feeling inferior to anyone, therefore the concept of racial hierarchy seemed somewhat alien to him.

This likely influenced his artistic practice, where he often explores the concept of class, and notably, his figures are devoid of racial markers like skin color or facial features. He deliberately aim to create a post-racial aesthetic.

This year at the Venice Biennale, his series Refugee Astronaut (2015-ongoing) introduces a life-sized nomadic astronaut adorned with ‘African’ fabric, equipped to navigate ecological and humanitarian crises. Carrying a mesh of possessions, the figure symbolises the challenges of displacement.

In a cautionary tone, Shonibare emphasises that the artwork serves as a warning, urging contemplation of the potential consequences of inaction regarding rising water levels and the resulting displacement of people.

Daniel Otero Torres, Aguacero, 2024, mixed media (photo private)

Aguacero, an ephemeral site-specific installations made of collected locally and recycled materials, reflects the Otero Torres’ engagement with the impact of ecological crises on the lives of marginalised Columbians.

The work evokes the peculiar system of vernacular stilt architecture of the communities along the banks of the Atrato River, designed to collect rainwater and provide the inhabitants with unpolluted water. Paradoxically, even they reside in one of the most rainfall-abundant regions, they face severe challenges in obtaining clean water due to extensive pollution caused by illegal gold mining.

Daniel Otero Torres, Aguacero, 2024, mixed media (photo private)

As a result, community members have created their own technological system. Through metaphorical recreation, Torres draws attention to the challenge of ensuring access to clean, drinkable water faced by communities worldwide an issue is intricately connected to the processes of privatizing and financializing nature.

As an open structure to the eyes of the world, this work reveals the sound journey of flowing water and its multiple meanings.

Trevor Yeung explores sentimentality, desire, and relationships of power through the concept of attachment, which manifests as feelings of connection with objects as well as a longing for someone special.

The exhibition articulates the artist’s intimate experiences and keen observations of the relationships between humans and aquatic systems, drawing from references that include his father’s seafood restaurant, pet shops, feng shui arrangements, and the fish he kept as a child.

Trevor Yeung, Cave of Avoidance (Not Yours), 2024. Installation view, Trevor Yeung: Courtyard of Attachments, Hong Kong in Venice, 2024 (photo private)

The exhibition consists of eleven new artworks, four of which are specific to Venice and respond to the architecture of the venue. Yeung articulates his fascination with artificiality in nature and urban space with aquariums that are fully operational but contain no fish.

Cave of Avoidance (Not Yours) is an immersive installation that recreates the interior of a pet shop, with aquariums devoid of fish. By omitting the fish from the meticulously arranged row of tanks, Yeung leads us to reconsider our motivations for creating artificial environments designed to condition or control other living beings.

Trevor Yeung, Cave of Avoidance (Not Yours), 2024. Installation view, Trevor Yeung: Courtyard of Attachments, Hong Kong in Venice, 2024

Yeung’s presentation seamlessly blends familiar elements of Hong Kong’s visual and material culture, creating an immersive environment that evokes profound emotional responses.

Walking through this eerily empty fish pet shop, I was transported back to my own childhood memories of Hong Kong, while simultaneously resonating with the current political climate, which, in its own way, also evokes a profound sense of emptiness and eerieness.

Reflections

After a day immersed in the art of Venice, there’s no finer way to conclude the evening than with a visit to the Aman.

Housed within a 16th-century palazzo, the hotel’s secluded location on the Grand Canal, away from the crowds, further enhances its sense of serenity.

Indulge in the perfect cocktail to contemplate your journey: the ‘Reflections’. As the menu eloquently describes, ‘the reflection of thought: a dedica to intimate and contemplative beauty. Like the painter who secretly paint his own face.’

Photos by Marc Lauterfeld